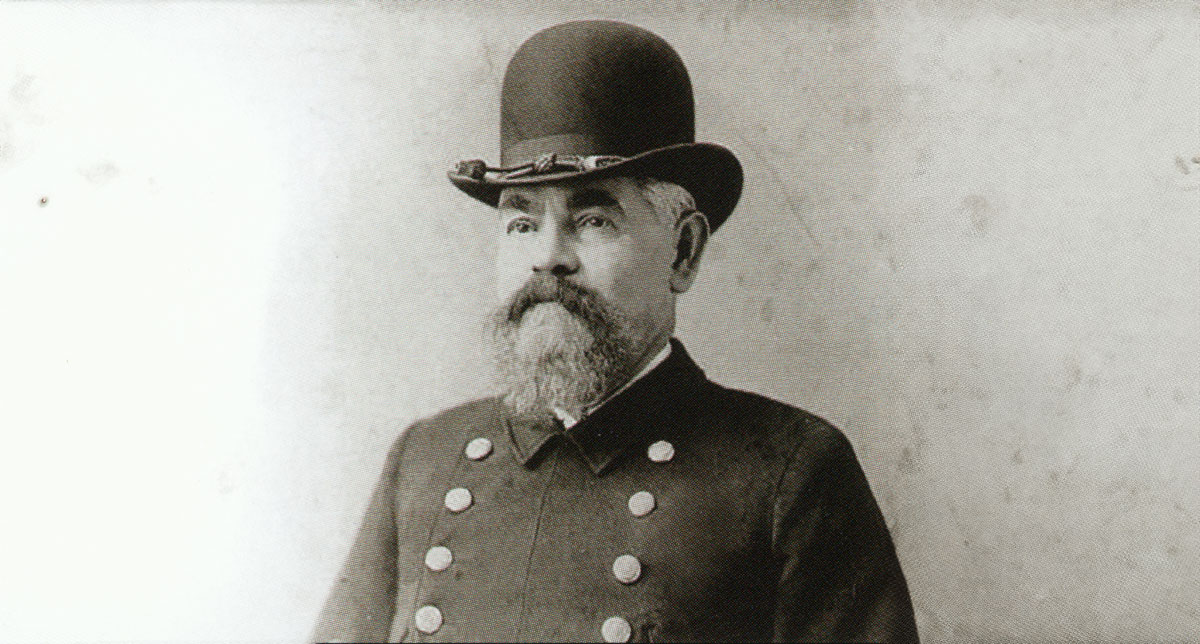

Nicholas Hunsaker was born August 7, 1825, in Alexander County, Illinois, the son of Daniel and Charlotte (King) Hunsaker. Hunsaker descended from Mennonites expelled from Switzerland and emigrated to Pennsylvania.

Nicholas settled in Contra Costa County, California in 1847, where he farmed and raised stock under the T5 brand, as well as serving as Sheriff of Contra Costa from 1851 to 1853 and again from 1855 to 1857.

Nicholas Hunsaker married Lois E. Hastings, and moved his family to San Diego in 1869, where they lived on their ranch in the Tia Juana Valley. He was elected Sheriff of San Diego County in 1875 and 1876.

Hunsaker was Sheriff at the time of the famous Gaskill Brothers Store shootout in Campo on December 4, 1875. This was a major shootout between a Mexican bandit band of six men, the Gaskill brothers (Silas and Lumen), a “Frenchman” who arrived on horseback, a local named “Livingston”, and the telegraph operator (a correspondent for the San Diego Union). The gunfight resulted in serious wounds to the Gaskills, but the bandits were routed, leaving two bandits dead and the others wounded or captured.

Sheriff Hunsaker arrived at Campo with three Deputies on December 5th and took two of the injured and captured Mexican bandits under guard. That night, while the Sheriff and two of the guards were away for a few minutes, or so it was reported, a group of ranchers appeared, tied up the remaining guard, and carried off the prisoners. The next morning some Mexicans from Tecate found the two bandits hanging from a tree by a single piece of rope.

On September 20, 1875, under orders from the District Court of San Francisco, Sheriff Nicholas Hunsaker of San Diego and approximately twenty armed men evicted the Temecula Indians from their traditional village. The eviction took place over three days and became famously known as “The Temecula Eviction”.

The posse led by Sheriff Hunsaker, who was paid $300 for the job, included the owners of the ranch, as well as local landowners Louis Wolf and José Gonzales. The men drove wagons to the Indians’ homes and loaded their belongings in them. The Indians did not fight back because the posse members told them that anyone who resisted would be shot.

The Temecula people protested by sitting down and refusing to move any of their belongings. Once the wagons were full, the people were forced to leave the village, following behind the wagons. They had to abandon their crops and most of their livestock. The posse shouted insults and threw stones to get them to move along. Once they were beyond the borders of the rancho, a hike of about three miles, the posse members emptied the wagons onto the ground. They were not careful, and they broke many of the people’s belongings, including pots that contained food. The evictees salvaged what they could and looked for a new place to go.

John Magee, one of Temecula’s early American settlers, invited the Temecula people to stay on his land until they figured out what to do. He owned a store near the place the Indians and their belongings had been dumped, and his wife, Custoria Nesecat, was a Temecula (Pechanga) Indian woman. Those who chose to stay on Magee’s land settled near the foothills where they had access to water. Others chose to live in nearby Pechanga Canyon.

Helen Hunt Jackson, the future author of “Ramona”, visited the Temecula people shortly after the eviction and interviewed people about what had happened. Jackson was working for the Bureau of Indians affairs at the time, and she was quick to send the story of the eviction and the evictees’ appalling living conditions to the U.S. Government. Her reports helped convince Congress to set aside land for the Pechanga Reservation, which was established by Executive Order on June 27, 1882 by President Chester A. Arthur.

Nicholas’ son, William (“Will”) Jefferson Hunsaker, became a well-known politician and attorney in San Diego and Los Angeles. In 1879, Will moved to Tombstone, Arizona, where he and his law partner Tom Fitch represented U.S. Marshal Wyatt Earp in several of the Southwest’s most infamous cases. Will returned to San Diego and was the San Diego District Attorney from 1882 to 1884. In 1887 Will was elected Mayor of San Diego, but left office in 1888 due to power struggles with the City Council.

Nicholas Hunsaker died in San Diego on September 13, 1913 from injuries he received after being struck by a streetcar. He was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in San Diego under a headstone with “California Pioneer of 1847”.